gri_2003_m_46_b01_f09_054

- Max. dissimilarity: 0.192

- Mean dissimilarity: 0.153

- Image votes: 0.0

Transcribers

- 65335099 - WiltedLotus

- 65352495 - sweezie

- WINNER - 65369599 - SaraEliz

- 65376276 - csleahey

- 65377813 - octodragon

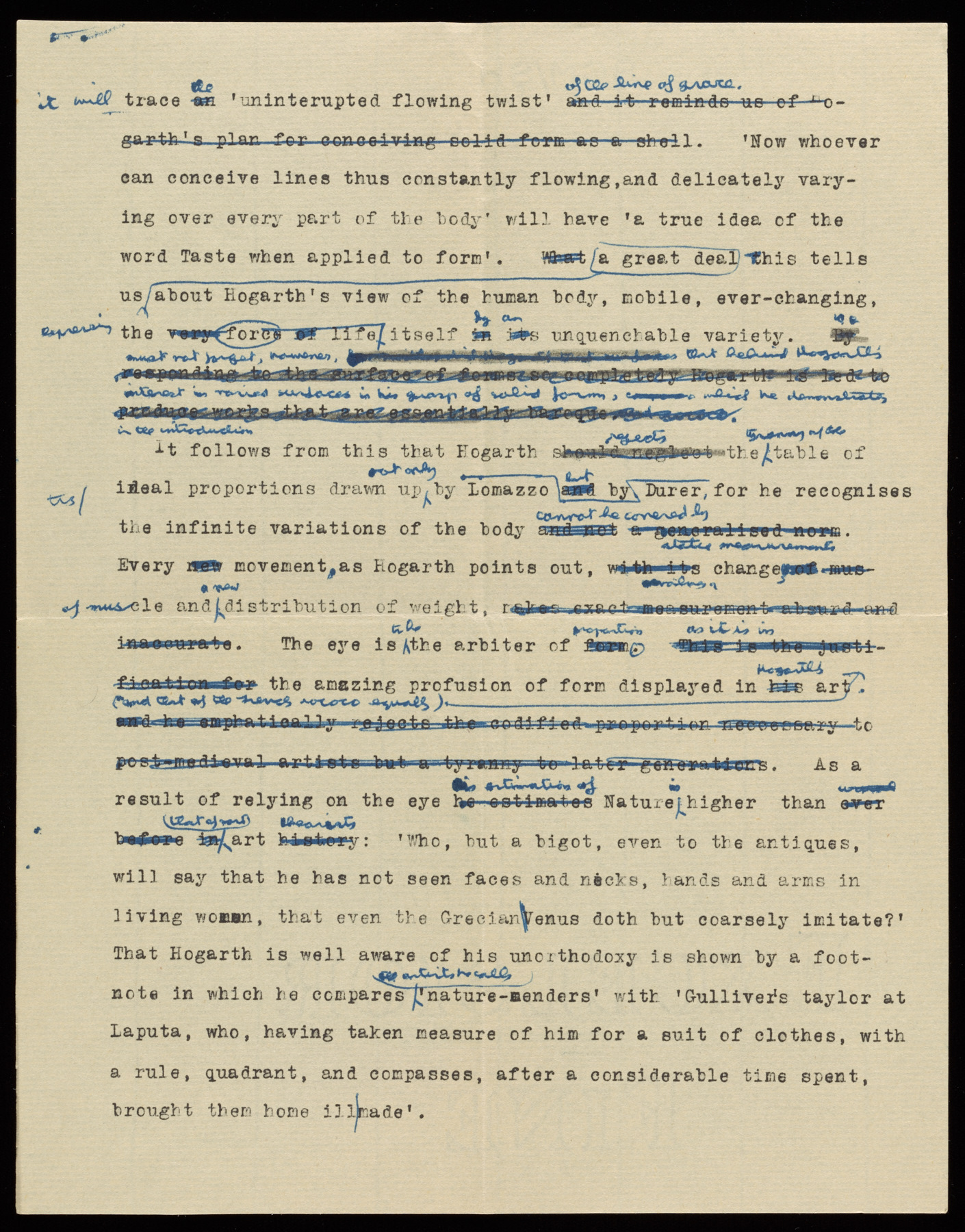

65335099 - WiltedLotus

it will trace the 'uninterrupted flowing twist' of the line of grace. 'Now whoever can conceive lines thus constantly flowing, and delicately varying over every part of the body' will have 'a true idea of the word Taste when applied to form'. This tells us a great deal about Hogarth's view of the human body, mobile, ever-changing, expressing the life-force itself by an unquenchable variety. We must not forget, however, that behind Hogarth's interest in varied surfacesis his grasp of solid form, which he demonstrates in the introduction.It follows from this that Hogarth rejects the tyranny of the table of ideal proportions drawn up not only by Lomazzo but by Durer, for he recognises the infinite variations of the body cannot be covered by every movement, as Hogarth points out, evolvingchanges of muscle and a new distribution of weight. The eye is the arbiter of proportions as it is in the amazing profusion of form displayed in Hogarth's (and that of the French rococo equally) art.As a result of relying on the eye his estimation of Nature is higher than that of new art theorists: 'Who, but a bigot, even to the antiques, will say that he has not seen faces and necks, hands and arms in living women, that even the Grecian Venus doth but coarsely imitate?' That Hogarth is well aware of his unorthodoxy is shown by a foot-note in which he compares artists he calls 'nature-menders' with 'Gulliver's taylor a Laputa, who, having taken measure of him for a suit of clothes, with a rule, quadrant, and compasses, after a considerable time spent, brought them home ill made'.

65352495 - sweezie

it will trace the 'uninterrupted flowing twist' of the line of grace. 'Now whoever can conceive lines thus constantly flowing, and delicately varying over every part of the body' will have 'a true idea of the word Taste when applied to form'. This tells us a great deal about Hogarth's view of the human body, mobile, ever-changing, expressing the life force itself by an unquenchable variety. We must not forget, however that behind Hogarth's interest in raised surfaces in his grasp of solid form, which he demonstrates in the introduction.I follows from this that Hogarth rejects the survey of the ideal proportions drawn up but only by Durer but by Lomazzo, for he recognises the infinite variations of the body cannot be covered by static measurements.

Every movement, as Hogarth points out, detailing change of muscle and a new distribution of weight. /the eye is to be the arbiter of proportion as it is in the amazing profusion of form displayed in Hogarths art and that of the themes[unclear[ rococo equals. As a result of relying on the eye his estimation of Nature is higher than that of most art theorists: 'Who, but a bigot, even to the antiques, will say that he has not seen faces and necks, hands and arms in living women, that even the Grecian Venus doth but coarsely imitate?'

That Hogarth is well aware of his unorthodoxy is shown by a footnote in which he compares all unintentionally ' nature - menders' with Gulliver's tailor at Laputa, who, having taken measure of him for a suit of clothes, with a rule, quadrant, and compasses, after a considerable time spent, brought them home ill made'.

WINNER - 65369599 - SaraEliz

it will trace the 'uninterrupted flowing twist' of the line of grace.'Now whoever

can conceive lines thus constantly flowing, and delicately varying

over every part of the body' will have 'a true idea of the

word Taste when applied to form'. This tells us a great deal

about Hogarth's view of the human body, mobile, ever-changing,

expressing the life-force itself by an unquenchable variety. We

must not forget, however, that behind Hogarth's

interest in varied surfaces in his grasp of solid form, which he demonstrates

in the introduction

It follows from this that Hogarth rejects the tyranny of the table of

ideal proportions drawn up out only by Durer but by Lomazzo, for he recognises

the infinite variations of the body cannot be covered by states measurements.

Every movement, as Hogarth points out, reveals a change,

of muscle and a new distribution of weight,

The eye is to be the arbiter of proportion. As it is in

the amazing profusion of form displayed in Hogarth's art.

(and that as the French rococo equally)

As a

result of relying on the eye his estimation of Nature is higher than

that of mart art theorists: 'Who, but a bigot, even to the antiques,

will say that he has not seen faces and necks, hands and arms in

living woman, that even the Grecian/Venus doth but coarsely imitate?'

That Hogarth is well aware of his unorthodoxy is shown by a footnote

in which he compares artists he calls 'nature menders' with 'Gulliver's taylor at

Laputa, who, havign taken measure of him for a suit of clothes, with

a rule, quadrant, and compasses, after a considerable time spent,

brought them home ill made'.

65376276 - csleahey

it will trace the 'uninterrupted flowing twist' of the line of grace. 'Now whoever can conceive lines thus constantly flowing, and delicately varying over every part of the body' will have a 'true idea of the word Taste when applied to form'. This tells us a great deal about Hogarth's view of the human body, mobile, ever-changing, expressing the force of life itself by an unquenchable variety. He must not forget, however that behind Hogarth's interest in varied scedaces in his grasp of solid form, which he demonstrates in the introduction.It follows from this that Hogarth rejects the table of ideal proportions drawn up not only by Lomazzo but by Durer, for he recognizes the infinite variations of the body cannot be covered by static measurements. Every movement, as Hogarth points out changes of muscle and a new distribution of weight. The eye is the arbiter of proportion. As it is in the amazing profusion of form displayed in Hogarth's art ("and that as to rococo equally. As a result of relying on the eye his estimation of Nature is higher than that of most art theorists: 'Who but a bigot, even to the antiques, will say that he has not seen faces and necks, hands and arms in living women, that even the Grecian Venus doth but coarsely imitate?' That Hogarth is well aware of the unorthodoxy is shown by a foot note in which he compares antithetically 'nature-menders' with 'Gulliver's taylor at Laputa, who, having taken measure of him for a suit of clothes, with a rule, quadrant, and compass, after a considerable time spent, brought them home ill made'.

65377813 - octodragon

it will trace the 'uninterupted flowing twist' of the line of grace.'Now whoever

can conceive lines thus constantly flowing, and delicately vary-

ing over ever part of the body' will have 'a true idea of the

word Taste when applied to form'. This tells

us a great deal about Hogarth's view of the human body, mobile, ever-changing,

expressing the life force itself by an unquenchable variety. We

must not forget, however, that behind Hogarth's

interest in various surfaces in his group of solid form, unlike he demonstrates

in the introduction.

It follows from this that Hogarth neglects the Granny of the table of

ideal proportions drawn up not only by Lomazzo but by Durer, for he recognises

the infinite variations of the body cannot be covered by alated measurements.

Every movement, as Hogarth points out, revealing changes

of muscle and a new distribution of weight.

The eye is to the arbiter of proportion, as it is in

the amazing profusion of form displayed in Hogarth's art (and that of the neves rococo equals .

As a

result of relying on the eye his estimation of Nature is higher than

that of new art theorists: 'Who, but a bigot, even to the antiques,

will say that he has not seen faces and necks, hands and arms in

living women, that even the Grecian Venus doth but coarsely imitate?'

That Hogarth is well aware of his unorthodoxy is shown by a foot-

note in which he compares all artists he calls 'nature-menders' with 'Gulliver's taylor at

Laputa, who, having taken measure of him for a suit of clothes, with

a rule, quadrant, and compasses, after a considerable time spent,

brought them home ill made'.