gri_2003_m_46_b06_f04_018

- Max. dissimilarity: 0.16

- Mean dissimilarity: 0.086

- Image votes: 0.0

Transcribers

- 73012604 - catuecker

- 73424610 - the3esses

- 73547609 - Zooniverse2017

- 73651968 - jesseytucker

- 73715474 - Chris5420

- WINNER - 73719294 - glt

73012604 - catuecker

The Atonement of Gosta Berling opens with slow shots, panning and fixe, of natural landscape - panoramic and with a sense of scale and light. Such slow treatment, with sluggish subtitle, when it finally comes is absurd - 'in the heart of the country': surprise! The subtitles, though the obscure plot needs them, continually jar: 'Why, Countess, what are you doing alone on the ice at night? The reader of Conrad and the reader of the New Yorker must join in finding these sub-titles grotesque and provicial. The images and the compositional sense of Maurice Stiller have grandeur but the nobility lurches continuuosly into bathos. Too many arms are raised to point at too many doors.The opening suggests the rightness of nature. The rhetoric of the human beings who soon appear is not devoid of insight - for example the Countess' monologue to Gosta is eloquently in envery gesture, and Greta Garbo's sensual face really makes something of the symbolic flight across the lake. However, the dragging of the plot, its perpetual detours and repetitions, does express a state of mind which soaks the film's texture. Grandeur becomes perversity in the lingering carressing anguish which is everybody's lot sooner than later. Large eyes look so often at the wreck of their life or hopes or on the past that a psychological malaise shadows the pantheistic landscape sense.

Perenenes or experrind, the ham-acting dirralve the present (the real images on the screen, that is) & sucks our attention back to rewote, casual guilt. Exasperation and admiration are comingled in one's reaction to this film, 30 years after it was made.

73424610 - the3esses

The Atonement of Gosta Berling opens with slow shots, panning and fixed, of natural landscape - panoramic and with a sense of scale and light. Such slow treatment, with sluggish fades, suggests reverence, perhaps for God-in-Nature. The 1st subtitle, when it finally comes is absurd - 'in the heart of the country': surprise! The subtitles, though the obscure plot needs them, continually jar: 'Why, Countess, what are you doing alone on the ice at night?' and so on. The reader of Conrad and the reader of the NEw Yorker must join in finding these sub-titles grotesque and provincial. The images and the compositional sense of Maurice Stiller have grandeur but the nobility lurches continually into bathes. Too many arms are raised to point at too many doors.The opening suggests the rightness of nature. The rhetoric of the human beings who soon appear is not devoid of insight - for example the Countess' monologue to Gosta is eloquent in every gesture, and Greta Garbo's sensual face really makes something of the symbolic flight across the lake. However, the dragging of the plot, its perpetual detours and repetitions, does express a state of mind which soaks the film's texture. Grandeur becomes perversity in the lingering carressing anguish which is everybody's lot sooner or later. Large eyes look so often at the wreck of their life or hopes or on the past that a psychological malaise shadows the pantheistic landscape sense.

Perversely to expressing the ham-acting dissolves the present (the real images on the screen, that is) & sucks our attention back to remote, causal guilt. Exasperation and admiration are thus mingled in one's reaction to this film, 30 years after it was made.

73547609 - Zooniverse2017

The Atonement of Gosta Berling opens with slow shots, pan-ning and fixed, of natural landscape - panoramic and with a

sense of scale and light. Such slow treatment, with sluggish

fades, suggests reverence, perhaps for God-in-Nature. The 1st

subtitle, when it finally comes is absurd - 'in the heart of

the country' - surprise! The subtitles, though the obscure

plot needs them, continually jar: 'Why, Countess, what are you

doing alone on the ice at night?' and so on. The reader of

Conrad and the reader of the New Yorker must go in finding

these subtitles grotesque and provincial. The images and the

compositional sense of Maurice Stiller have grandeur but the

nobility lurches continually into bathos. Too many arms are

raised to point at too many doors.

The opening suggests the rightness of nature. The rhetoric

of the human beings who soon appear is not devoid of insight -

for example, the Countess' monologue to Gosta is eloquent in every

gesture, and Greta Garbo's sensual face really makes something

of the symbolic flight across the lake. However, the drag-

ging of the plot, its perpetual detours and repetitions, does

express a state of mind which soaks the film's texture. Grand-

eur becomes perversity in the lingering caressing anguish which

is everybody's lot sooner or later. Large eyes look so often

at the wreck of their life or hopes or on the past that a psycho-

logical malaise shadows the pantheistic landscape sense.

Perversely by expressing the ham-acting dissolves the present (the real

image on the screen, that is) & sucks our attention back to private,

causal guilt. Exasperation and admiration are thus mingled in

one's reaction to this film, 30 years after it was made.

73651968 - jesseytucker

The Atonement of Gosta Berling opens with slow shots, pan-ing and fixed, of natural landscape--panoramic and with a

sense of scale and light. Such slow treatment, with sluggish

fades, suggests reverence, perhaps for God-in-Nature. The 1st

subtitle, when it finally comes is absurd--'in the heart of

the country': surprise! The subtitles, though the obscure

plot needs them, continually jar: 'Why, Countess, what are you

doing alone on the ice at night?' and so on. The reader of

Conrad and the reader of the New Yorker must join in finding

these sub-titles grotesque and provincial. The images and the

compositional sense of Maurice Stiller have grandeur but the

nobility lurches continually into bathos. Too may arms are

raised to point at too many doors.

The opening suggests the rightness of nature. The rhetoric

of the human beings who soon appear is not devoid of insight--

for example the Countess' monologue to Gosta is eloquent in every

gesture, and Greta Garbo's sensual face really makes something

of the symbolic flight across the lake. However, the drag-

ging of the plot, its perpetual detours and repetitions, does

express a state of mind which soaks the film's texture. Grand-

eur becomes perversity in the lingering carressing anguish which

is everybody's lot sooner or later. Large eyes look so often

at the wreck of their life or hopes or on the past that psycho-

logical malaise shadows the pantheistic landscape sense.

Permananetly and expressingly the ham acting dissolves the present (the real

images on the screen, that is) to sucks our attention back to newate,

casuea guilt, exasperation and admiration are thus mingled in

one's reaction to this film, 30 years after it was made.

73715474 - Chris5420

The Atonement of Gosta Berling opens with slow shots, pan-ning and fixed, of natural landscape - panoramic and with a sense of scale and light. Such slow treatment, with sluggish fades, suggests reverence, perhaps for God-in-Nature. The 1st subtitle, when it finally comes is absurd - 'in the heart of the country': surprise! The subtitles, though the obscure plot needs them, continually jar: 'Why, countess, what are you doing alone on the ice at night?' and so on. The reader of Conrad and the reader of the New Yorker must join in finding these sub-titles grotesque and provincial. The images and the compositional sense of Maurice Stiller have grandeur but the nobility lurches continually into bathos. Too many arms are raised to point at too many doors.The opening suggests the rightness of nature. The rhetoric of the human beings who soon appear is not devoid of insight - for example the Countess' monologue to Gosta is eloquent in every gesture, and Greta Garbo's sensual face really makes something of the symbolic flight across the lake. However, the drag-ging of the plot, its perpetual detours and repetitions, does express a state of mind which soaks the film's texture. Grand-eur becomes perversity in the lingering carressing anguish which is everybody's lot sooner or later. Large eyes look so often at the wreck of their life of hopes or on the past that a psycho-logical malaise shadows the pantheisitic landscape sense.

Perversely & expressively the ham-acting dissolves the present (the real images on the screen, that is) & sucks our attention back to remote causal guilt. Exasperation and administration are thus mingled in one's reaction to this film, 30 years after it was made.

WINNER - 73719294 - glt

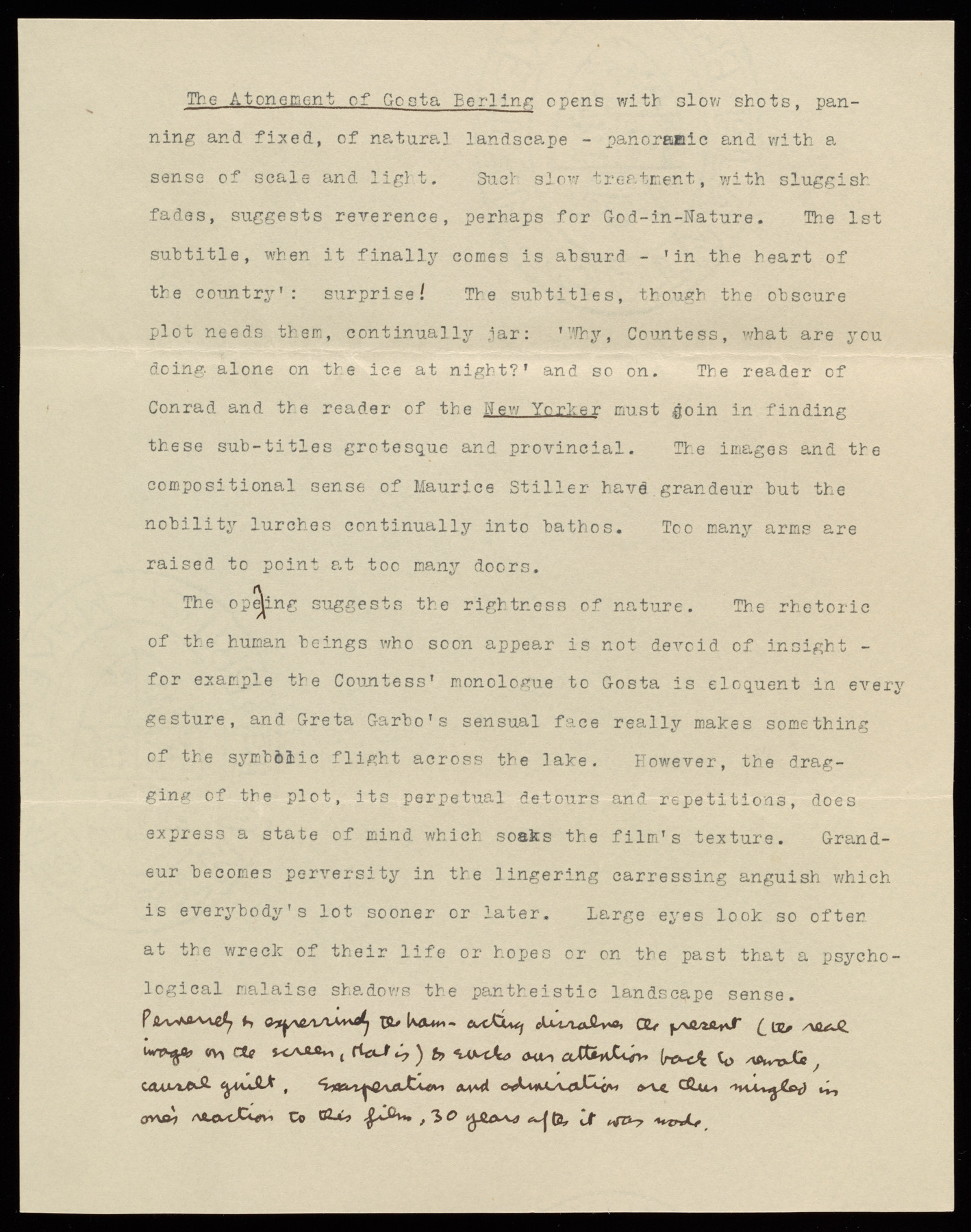

The Atonement of Gosta Berling opens with slow shots, panning and fixed, of natural landscape - panoramic and with a sense of scale and light.Such slow treatment, with sluggish fades, suggests reverence, perhaps for God-in-Nature.

The 1st subtitle, when it finally comes is absurd - 'in the heart of the country': surprise! The subtitles, though the obscure plot needs them, continually jar: 'Why, Countess, what are you doing alone on the ice at night?' and so on. The reader of Conrad and the reader of the New Yorker must join in finding these sub-titles grotesque and provincial. The images and the compositional sense of Maurice Stiller have grandeur but the nobility lurches continually into bathos. Too many arms are raised to point at too many doors.

The opening suggests the rightness of nature. The rhetoric of the human beings who soon appear is not devoid of insight - for example the Countess' monologue to Gosta is eloquent in every gesture, and Greta Garbo's sensual face really makes something of the symbolic flight across the lake. However, the dragging of the plot, its perpetual detours and repetitions, does express a state of mind which soaks the film's texture. Grandeur becomes perversity in the lingering caressing anguish which is everybody's lot sooner or later. Large eyes look so often at the wreck of their life or hopes or on the past that a psychological malaise shadows the pantheistic landscape sense.

Perversely & expressively the ham-acting dissolves the present (the real images on the screen, that is) & sucks our attention back to remote, causal guilt. Exasperation and admiration are thus mingled in one's reaction to this film, 30 years after it was made.