gri_2003_m_46_b05_f09_040

- Max. dissimilarity: 0.117

- Mean dissimilarity: 0.064

- Image votes: 0.0

Transcribers

- 68874123 - JanetCormack

- 69133201 - jesseytucker

- 69372928 - not-logged-in-c349e7749bd8c358e295

- WINNER - 69677400 - tinkapuppy

- 70062847 - Zooniverse2017

- 70955532 - glt

68874123 - JanetCormack

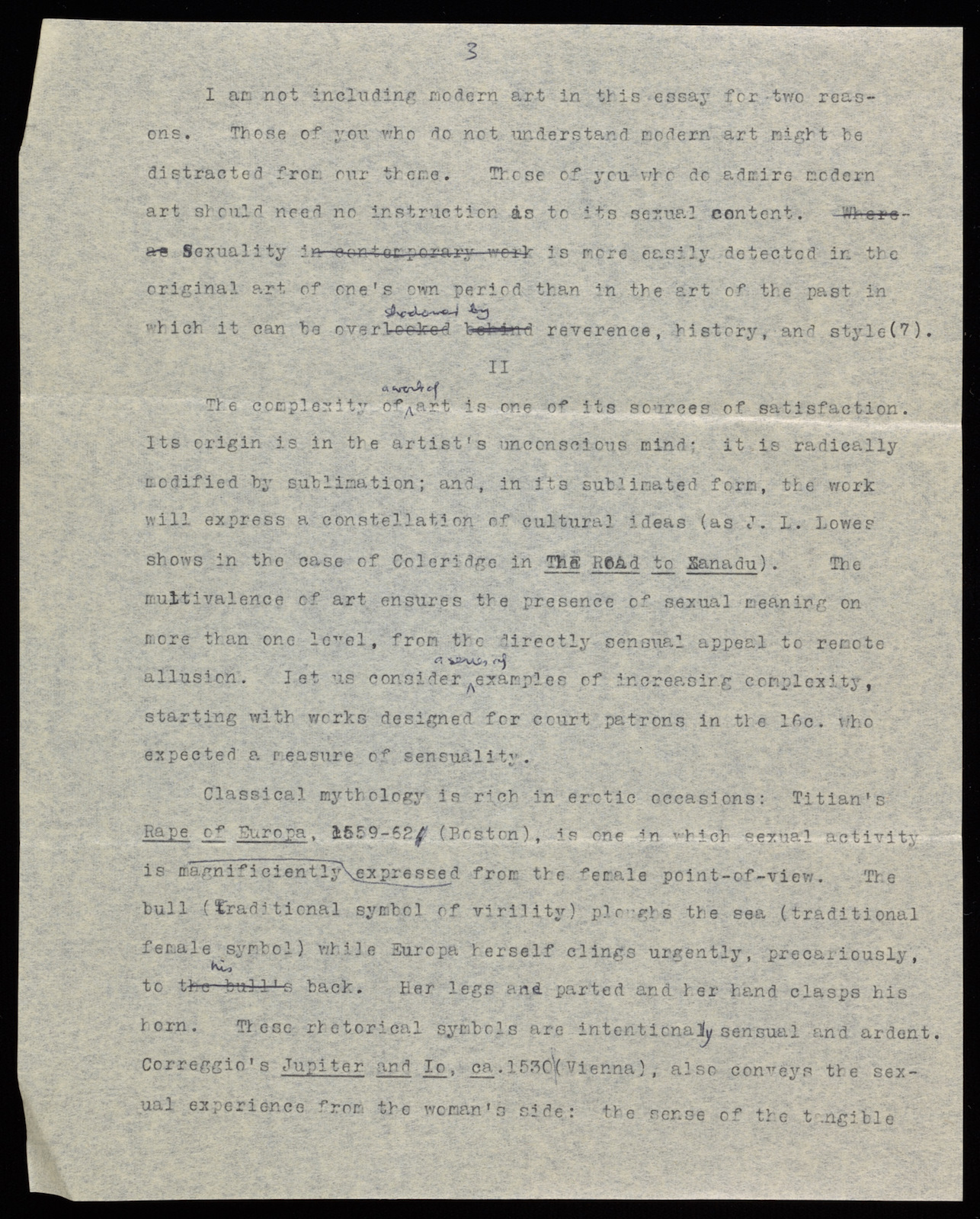

3I am not including modern art in this essay for two reasons. Those of you who do not understand modern art might be distracted from our theme. Those of you who do admire modern art should need no instruction as to its actual content. Sexuality is more easily detected in the original art of one's own period than in the art of the past is which it can be overshadowed by reverence, history and style(?)

II

The complexity of a work of art is one of its sources of satisfaction. Its origin in the artist's unconscious mind: it is radically modified by sublimation; and, in its sublimated form, the work will express a constellation of cultural ideas (as J. L. Lowes shows in the case of Coleridge in The Road to Xanadu). The multivalence of art ensures the presence of sexual meaning on more that one level, from the directly sensual appeal to remote allusion. Let us consider a series of examples of increasing complexity, starting with works designed for court patrons in the 16c who expected a measure of sexuality.

Classical mythology is rich in erotic occasions: Titian's Rape of Europa, 1559-62 (Boston), is one in which sexual activity is expressed magnificently from the female point-of-view. The bull (traditional symbol of virility) ploughs the sea (traditional female symbol) while Europa herself clings urgently, precariously, to his back. Her legs are parted and her hand clasps his horn. These rhetorical symbols are intentionally sensual and ardent. Correggio's Jupiter and Io, ca. 1530 (Vienna), also conveys the sexual experience from the woman's side: the sense of the tangible

69133201 - jesseytucker

3I am not including modern art in this essay for two reas-

ons. Those of you who do not understand modern art might be

distracted from our theme. Those of you who do admire modern

art should need no instruction in to its sexual content.

Sexuality is more easily detected in the

original art of one's own period than in the art of the past in

which it can be overshadowed by reverence, history, and style (?).

II

The complexity of awoked art is one of its sources of satisfaction.

Its origin is in the artist's unconscious mind: it is radically

modified by sublimation; and, in its sublimated form, the work

will express a constellation of cultural ideas (as C. L. Lowes

shows in the case of Coleridge in The Road to Xanadu). The

multivalence of art ensures the presence of sexual meaning on

more than one level, from the irectly sensual appeal to remote

allusion. Let us consider a series of examples of increasing complexity,

starting iwth works desinged for court patrons in the 16c. who

expected a measure of sensuality.Classical mythology is rich in erotic occasions: Titian's

Rape of Europa, 1559-62 (Boston), is one in which sexual activity

is expressed magnificently from the female point-of-view. The

bull (traditional symbol of virility) ploughs the sea (traditional

female symbol) while Europa herself clings urgently, precariously,

to the back. Her legs are parted and her hand clasps his

horn. These rehtorical symbols are intentinally sensual and ardent.

Crreggio's Jupiter and Io, ca. 1530 (Vienna), also conveys the sex-

ual experience from the woman's side: the sense of the tangible

69372928 - not-logged-in-c349e7749bd8c358e295

3I am not including modern art in this essay for two reas-

ons. Those of you who do not understand modern art might be

distracted from our theme. Those of you who do admire modern

art should need no instruction as to its sexual content.

Sexuality is more easily detected in the

original art of one's own period than in the art of the past in

which it can be overshadowed by reverence, history, and style (7).

II

The complexity of a work of art os one of its sources of satisfaction.

Its origin is in the artist's unconcious mind; it is radically

modified by sublimation; and, in its sublimated form, the work

will express a constellation of cultural ideas (as J.L. Lowes

shows in the case of Coleridge in The Road to Xanadu). The

multivalence of art ensures the presence of sexual meaning on

more than one level, from the directly sensual appeal to remote

allusion. Let us consider a series of examples of increasing complexity,

starting with works designed for court patrons in the 16c. who

expected a measure of sensuality.

Classical mythology is rich in erotic occasions: Titian's

Rape of Europa, 1559-62 (Boston), is one in which sexual activity

is magnificiently expressed from the female point-of-view. The

bull (traditional sybol of virility) ploughs the sea (traditional

female symbol) while Europa herself clings urgently, precariously,

to his back. Her legs are parted and her hand clasps his

horn. These rhetorical symbols are intentionally sensual and ardent.

Correggio's Jupter and Io, ca. 1530 (Vienna), also conveys the sex-

ual experience from the woman's side: the sense of the tangible

WINNER - 69677400 - tinkapuppy

3I am not including modern art in this essay for two reas-

ons. Those of you who do not understand modern art might be

distracted from our theme. Those of you who do admire modern

art should need no instruction as to its sexual content.

Sexuality is more easily detected in the

original art of one's own period than in the art of the past in

which it can be overshadowed by reverence, history, and style. (7)

II

The complexity of a work of art is one of its sources of satisfaction.

Its origin is in the artist's unconscious mind: it is radically

modified by sublimation; and, in its sublimated form, the work

will express a constellation of cultural ideas (as J.L. Lowes

shows in the case of Coleridge in The Road to Xanadu). The

multivalence of art ensures the presence of sexual meaning on

more than one level, from the directly sensual appeal to remote

allusion. Let us consider a series of examples of increasing complexity,

starting with works designed for court patrons in the 16c. who

expected a measure of sensuality.

Classical mythology is rich in erotic occasions: Titian's

Rape of Europa, 1559-62 (Boston), is one in which sexual activity

is expressed magnificently from the female point-of-view. The

bull (traditional symbol of virility) ploughs the sea (traditional

female symbol) while Europa herself clings urgently, precariously,

to his back. Her legs are parted and her hand clasps his

horn. These rhetorical symbols are intentionally sensual and ardent.

Correggio's Jupiter and Io, ca. 1530 (Vienna), also conveys the sex-

ual experience from the woman's side: the sense of the tangible

70062847 - Zooniverse2017

3I am not including modern art in this essay for two reas-

ons. Those of you who do not understand modern art might be

distracted from our theme. Those of you who do admire modern

art should need no instruction as to its sexual content.

Sexuality is more easily detected in the

original art of one's own period than in the art of the past in

which is can be overshadowed by reverence, history and style(7).

II

The complexity of a work of art is one of its sources of satisfaction.

Its origin is in the artist's unconscious mind: it is radically

modified by sublimation; and, in it sublimated form, the work

will express a constellation of cultural ideas (as J. L. Lowes

shows in the case of Coleridge in The Road to Xanadu). The

multivalence of art ensures the presence of sexual meaning on

more than one level, from the directly sensual appeal to remote

allusion. Let us consider a series of examples of increasing complexity,

starting with works designed for court patrons in the 16c. who

expected a measure of sensuality.

Classical mythology is rich in erotic occasionas: Titian's

Rape of Europa, 1559-62 (Boston), is one in which sexual activity

is expressed magnificently from the female point-of-view. The

bull (traditional symbol of virility) ploughs the sea (traditional

female symbol) while Europa herself clings urgently, precariously,

to his back. Her legs are parted and her hand clasps his

horn. These rhetorical symbols are intentionally sensual and ardent.

Correggio's Jupiter and Io, ca. 1530 (Vienna), also conveys the sex-

ual experience from the woman's side: the sense of the tangible

70955532 - glt

3I am not including modern art in this essay for two reasons. Those of you who do not understand modern art might be distracted from our theme. Those of you who do admire modern art should need no instruction as to its sexual content. Sexuality is more easily detected in the original art of one's own period than in the art of the past in which it can be overshadowed by reverence, history and style (7).

II

The complexity of a work of art is one of its sources of satisfaction. Its origin is in the artist's unconscious mind; it is radically modified by sublimation; and, in its sublimated form, the work will express a constellation of cultural idaeas (as J. L. Lowes shows in the case of Coleridge in The Road to Xanadu). The multivalence of art ensure the presence of sexual meaning on more than one level, from the directly sensual appeal to remote allusion. Let us consider a series of examples of increasing complexity, starting with works designed for court patrons in the 16c. who expected a measure of sensuality.

Classical mythology is rick in erotic occasions: Titian's Rape of Europe, 1559-62 (Boston), is one in which sexual activity is magnificently expressed from the female point-of-view. The bull (traditional symbol of virility) ploughs the sea (traditional female symbol) while Europa herself clings urgently, precariously, to his back. Her legs are parted and her hand clasps his horn. These rhetorical symbols are intentionally sensual and ardent. Correggio's Jupiter and Io, ca.1530 (Vienna), also conveys the sexual experience from the woman's side; the sense of the tangible